Considerations for drought response by local authorities

Local authorities in Australia are facing increasing frequencies of natural disasters and the drought, floods, bushfires and coranavirus pandemic of 2020 represent the most extreme events on record in many jurisdictions.

Diverting resources to secure assets and safeguard communities for increasingly longer periods in the face of these disasters places day-to-day operations of local authorities under additional stress. This has obvious implications for Council budgets, and in many cases, for state government emergency support and relief funding.

It is therefore important that we continuously reflect, review and reconsider how we prepare for these natural disasters and how we respond to them when they occur.

I reflected personally on the horrors of the 2019/2020 drought and bushfires in the February edition of QLD Source, questioning the role we play in the water sector as Custodians of Country — for all the good that we do, there is still more to learn, so much for us to adapt to, so much that we need to change, to ensure we have a sustainable water future.

Many local authorities across Queensland have continued their 2019 drought response efforts throughout 2020, recognising that welcome rains for some areas between January and March, and scattered, wild storms at the start of the 2020/2021 summer, have not improved long-term water security.

In South-East Queensland for example, the trigger for drought response actions (the 60% level of the 12 key bulk water storages) has been reached again, and important drought preparations are underway, despite forecasts of higher than average rainfall across Queensland resulting from the La Ninã phenomenon developing in the north-west Pacific.

Local authorities as a water user

With this situation as context, I thought it was opportune to reflect on the response of local authorities to drought as a water user. There is obvious emphasis in drought response on the role of local authorities as the manager and operator of storage, treatment and distribution systems, as well as their critical role in communication with customers, but there is also much to do in respect of managing their role as a water user.

In South-East Queensland, there is a unique arrangement for water services, but the emphasis in this article is on the role of councils across the State as water users, aside from their roles as water service entities. It is important that water conservation actions expected of communities in drought response, are also implemented by local authorities and that they lead the way in demonstrating responsible practice. Key areas for consideration include the following:

- Managing the efficiency of water use for public services, amenities and local authority operations.

- Developing an integrated water management (IWM) approach that leverages all available water sources in offsetting potable water demands.

- Developing strategies that are not simply evaluated on the basis of the capital and operating cost, but also reflect the value of water and the importance of developing long-term offsets to potable water consumption.

- Ensuring that the objectives and responsibilities for water demand management are embedded and appropriately resourced and funded within local authority operations and across all departments.

Typical public facilities representing high water demands

The wide range of facilities typically under local authority control represent a demanding operational task. Ensuring optimal and efficient water use at these facilities requires significant planning across council operations to be effective and sustainable. Types of facilities would vary from one council to another, but could include the following:

- Public parks — with water amenities (e.g. splash pools, ponds, etc.), toilet facilities, lawn and flower bed irrigation systems.

- Botanic gardens — which require substantial irrigation, and may include plants of state significance requiring special care.

- Sports complexes — with field irrigation systems, swimming pools, kitchen, change-room and toilet facilities.

- Works depots and workshops — for operations dealing with parks and grounds, roads and stormwater, etc., and could include vehicle washing and dust suppression systems.

- Quarries and asphalt plants.

- Solid waste and recycling depots, waste transfer stations.

- Bus depots — these may not be under the direct control of a council, but bus washing is a high water demand activity.

- Cemeteries — operational cemeteries often include irrigation systems for general grounds and memorial gardens.

- Standpipes — both for large tanker filling (could be potable or non-potable facilities) and smaller scale demands for building sites.

- Council administration buildings.

- Potable water demands at water and sewage treatment plants (if within Council jurisdiction).

Managing water use efficiency

Water-use efficiency of customers is a key focus in drought response strategies, but is often not an operational objective of councils in respect of their own water use, which can make the transition to an active state of water management difficult. To effectively and sustainably manage water-use efficiency, the following are critical:

- A metering and sub-metering strategy — the old adage that you can’t manage water if you don’t measure it, applies in every respect. Main meters measure demands from the "town water supply" and sub-meters track demands across different parts of the facility.

- A meter reading regime — to include archiving of meter readings for historic analysis and meter reading at a meaningful frequency. The advent of low-cost smart meters and low-cost data loggers on conventional meters, makes this an affordable and easily implemented objective, making a significant difference to providing meaningful data for water use efficiency management. There is very little that can be done with quarterly meter volumes, but hourly data (for example) will provide insights into water use that can drive improvements in water-use efficiency.

- Track water leakage trends — this is a critical action, all but impossible with quarterly meter read data. Even daily meter reads would provide evidence of major leaks and trends. Background leakage trends would require meter read records over a longer period of time (weeks and months).

- A thorough inventory of water use points and operations — e.g. meter sizes and types, WELS rating of plumbing fixtures, but also the nature of water use activities such as bus washing equipment or irrigation control systems.

- An accessible and up-to-date archive of facility record drawings — as-constructed drawings are critical for future reference to facilities and systems.

- Maintaining water service schematics — indicating water-use zones, meter locations and current operations at the facility. If non-potable water sources form part of the facility services, these can be quickly referenced.

- Developing water balances to track areas of significant water use across a facility and monitor trends over time.

- Recording changes in operations at a facility that may influence water demands and record-keeping. A case in point could be a meter change-out, where end and start readings and serial numbers of the old and new meters respectively are critical to interpreting meter read data.

- Collate industry benchmarks for water consumption across all the facility types and cross-check current consumption relative to these benchmarks — this will serve the immediate purpose of prioritising actions.

All of the above elements are meaningless without responsibility and obligation being assigned to key people in councils to operate and maintain systems, to collate, analyse and report on water use practice, and to plan for continuous improvement. This requires integrated efforts across many council departments, towards a clearly articulated goal of being a responsible and accountable water consumer. The management process requires clear definition of roles and responsibilities, and data management and reporting will require software or programs to facilitate the analysis and reporting.

Key focus areas for improving water efficiency

It is stating the obvious that a thorough understanding of the facility and its operations in respect of water demands, leveraging the issues addressed above in management practice, is critical before options to improve water-use efficiency can be developed, assessed and implemented. Typical areas of intervention include the following:

- Use of the results of facility benchmarking, develop plans to bring facilities with apparent excessive demands into line with best practice.

- Installation of automatic irrigation control systems, together with soil moisture sensors, to optimally irrigate fields and gardens.

- Installation of meters with data loggers (or smart meters), integrated with meter management systems, to track site water demands.

- Implementation of replacement programs for non-WELS rated plumbing fixtures.

- Identification and repair all system and plumbing leaks.

- Working with tenants (e.g. sports clubs) to track water demands and implement demand reduction programs.

- Development of IWM strategies to comprehensively assess rainwater and stormwater harvesting and recycled water use options to offset potable water demands. Large roof areas, in moderate to high rainfall areas, can yield significant volumes of water for Council operations. Stormwater harvesting is best suited to the irrigation of parks and depot wash-downs, although may require some form of treatment, increasing operating costs. Developing non-potable water sources may not always prove to be "cost-effective" against current town water tariffs, but should be assessed as a commitment to sound water stewardship with longer-term potable demand offsets in mind. This may require accepting pay-back periods of up to 20 years, but will provide important examples demonstrating the value of water to the broader community.

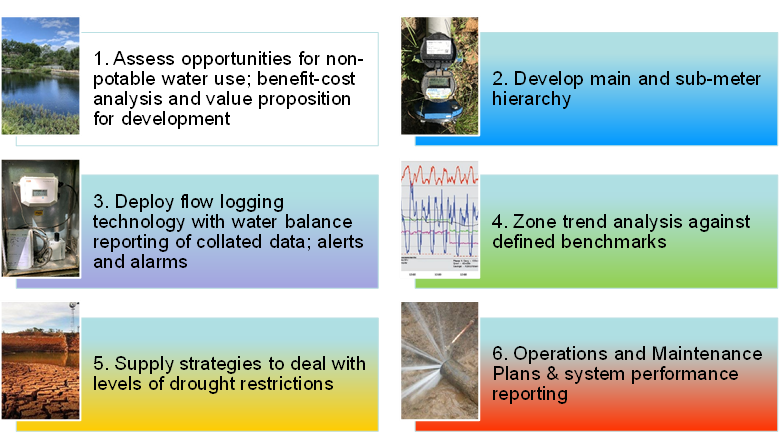

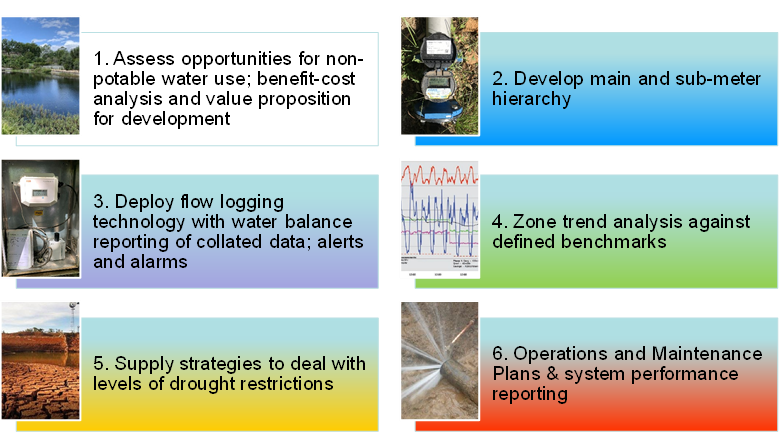

Particular facility plans would be sector and site-specific, and would reflect a Council’s IWM and water efficiency strategies. Facility plans could comprise elements presented in Figure 1.

Way forward

Developing a strategy for local authorities, appropriate to their operations and water-use levels, is fundamental to improving water-use efficiency across its operations, but also to sustaining any improvements that are made. The strategy would assign responsibility and accountability, but more importantly, empower departments to effectively manage their water demands, and would openly communicate the status quo.

What is important for future drought response actions is that local authorities can demonstrate their role as a responsible water user, aside from their role in managing water resources, treatment and distribution systems and restriction regimes for the communities they serve.

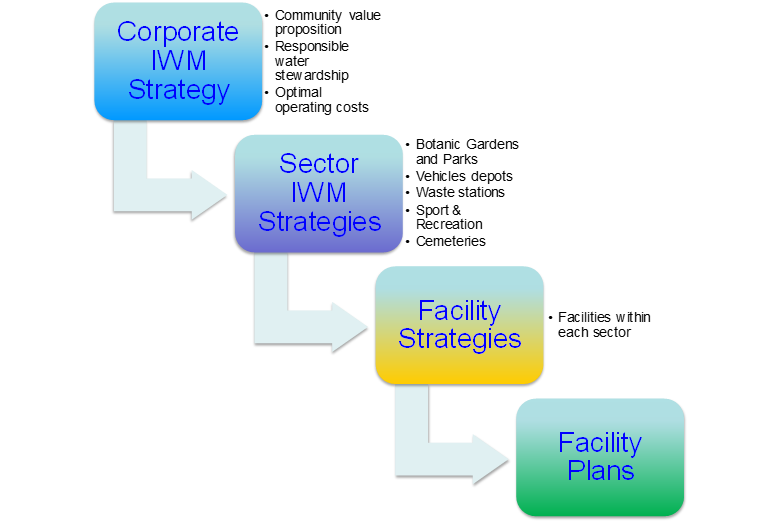

An approach to developing and implementing a strategy for water use efficiency management is outlined in Figure 2.